By: Silvia Santos, a leader of the IWU-FI

By: Silvia Santos, a leader of the IWU-FI

This text is based on the writings of Nahuel Moreno, Latin American and international Trotskyist leader, contained in the book «China from the Revolution to the Capitalist Restoration», in which he polemizes, together with other authors, with the leadership of the Fourth International, the United Secretariat.

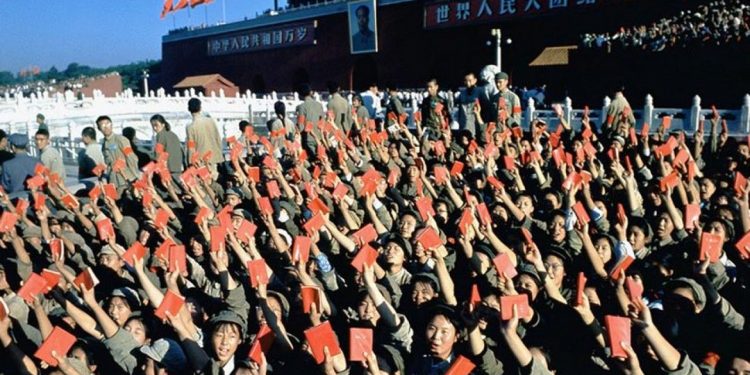

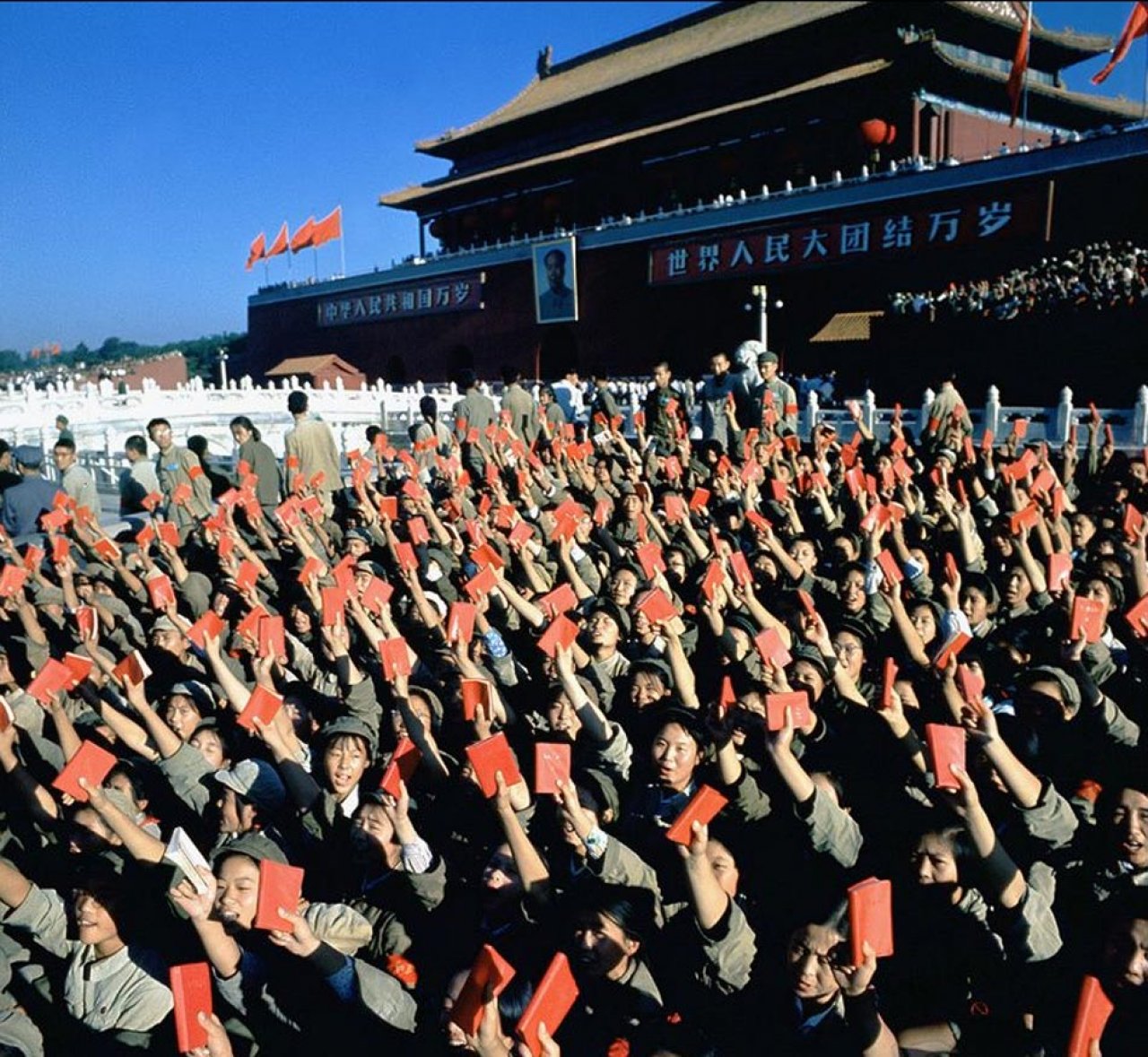

Most of the young fighters that get in touch with the revolutionary activism know very little about the Chinese Cultural Revolution that took place 54 years ago. The most symbolic images we keep of that process are the thousands or millions of young people demonstrating with «Mao Little Red Book» in their hands, which contained the leader’s quotes and speeches.

This movement, which attracted the world’s vanguard’s attention, had more than one interpretation. For some, it was a genuine manifestation of a new democracy emerging from below. For others, on the contrary, it expressed a fierce struggle between two sectors of the bureaucracy. Our current, headed by Nahuel Moreno, understood that it was an inter-bureaucratic struggle. One of these sectors, led by Mao Tse Tung and Lin Piao and supported by the mobilisation of the youth and the workers, led the Cultural Revolution.

The Chinese Revolution

On 1 October 1949, the Red Army entered Beijing, defeating the Kuomintang, the party of the landowners, the bourgeoisie and the rich peasants, which was supported by imperialism. Defeated by Chiang Kai-shek, the bloodthirsty dictator and leader of the Kuomintang, after a prolonged guerrilla war, the Chinese Communist Party, led by Mao, took power. At the head of the National Liberation Army, the Chinese Communist Party carried out a massive agrarian revolution, with the peasantry as its axis.

That this great revolutionary process was led by the peasantry, and therefore in the absence of workers’ democracy, gave Maoism a bureaucratic character. However, despite the limitations, a combination of the aim internal process and the international situation generated in the post-war period, pushed for the expropriation of the bourgeoisie, even though this task was not part of the program of the Chinese CP. (1.1)

For Mao, the revolution in China was anti-feudal and anti-imperialist, led by a «four-class bloc»: proletariat, peasants, urban petty bourgeoisie and national bourgeoisie. Despite differences with Stalinism, Maoism, like the bureaucracy of the USSR, advocated alliances with the national bourgeoisie and socialism in one country. The sweeping process of an agrarian revolution being carried out by millions of peasants, in a country that had a population of 700 million, had to stop at the democratic task of overthrowing the Kuomintang dictatorship.

But no matter how hard Mao tried to keep the revolution within the democratic framework, the logic of the agrarian revolution with millions of peasants occupying land gave rise to a workers’ and peasants’ government. Moreno pointed out the importance of the international framework. He reminds us that while the Stalinist counter-revolution took place in the years of mass retreat and victories against revolutionaries, from 1923 to 1943, the Chinese revolution took place in the period following the Second World War, accompanying the process of triumphant anti-colonial struggles and revolutions that, like the Yugoslav or Cuban ones, took place independently from the counter-revolutionary apparatus of Moscow.

Cultural Revolution

It is only within this framework that we will understand the meaning of the cultural revolution. It expressed the confrontation that broke out between the masses of youths and workers against the bureaucratic apparatuses, generating a crisis in the regime, with the questioning of the leadership. In that scenario, an inter-bureaucratic struggle started. To carry out his fight, Mao relies on the mobilisation of the youth and alleges that there are capitalist elements infiltrating the government. With this accusation, he insists that the revisionists should be defeated through class struggle.

The Youth responded to Mao’s call by forming Red Guard groups throughout the country. The movement spread to the army, the urban workers and the Communist Party leadership itself. This process opened up a series of factional struggles, widespread in all walks of life. At the top, it led to a massive purge of senior officials, particularly Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping. During the same period, Mao’s personality cult grew to gigantic proportions.

Begun in 1966, by January 1967 it had become such a mass mobilisation throughout the country that it was also beginning to involve urban working-class sectors. It was then that Mao, seeing that the process could get out of control, in 1969 tried to end the «Cultural Revolution» that had allowed him to eliminate his enemies and reaffirm himself as the leader of the Revolution. However, the process continued until his death in September 1976. With the death of the leader, China took another direction. The arrest of his successors, known as the Gang of Four, among whom was Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, and the Cultural Revolution finally ended.

From there, a new process began where the «reformers», led by the rehabilitated Deng Xiaoping, dismantled the scaffolding on which Maoism had been built. In 1978, Deng became the new leader from which a phase of reforms and economic opening would begin. A phase which had been initiated by Mao himself during Richard Nixon’s visit to China in 1972.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

China, a capitalist dictatorship

In the last work written by Moreno about China in International Correspondence 13, 1985, he reviews the rightward shift of the Chinese regime and the turn towards conciliation with the American imperialism started by Mao in the 1970s. With his successor Deng Xiaoping, that turn to the right will become impetuous and the opening to capitalism will take place without return.

In 2008, the work of Miguel Sorans, (a leader of the IWU-FI) takes up again the evolution of the Chinese process, on the way to restoration by turning China into a great capitalist economy. In Russia, Germany and the rest of the Eastern European countries, where the mass movement overthrew the bureaucratic dictatorships, it was the crushing of the mobilisations of millions of young students and workers, with the massacre of thousands of young people in May 1989 in Tiananmen Square, which explains why 70 thousand multinationals have settled in China, and it was considered «the factory of the world.

The work concludes with the characterisation of the Chinese state as capitalist and its regime as a dictatorship based on the Communist Party. It also highlights the innumerable workers’ and popular struggles that are spontaneously taking place in all corners of that immense country.

The future of China will depend on the impact of the world economic crisis and the current covid-19 pandemic in the country, and on the development of the class struggle. We end this text with a call to the world revolutionaries to support the struggles of the Chinese working class and youth for their demands and to speak out for the end of the Chinese capitalist dictatorship.