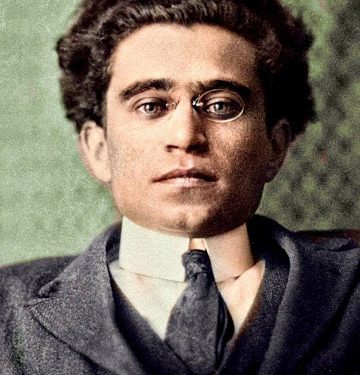

The Italian revolutionary died on 27 April 1937, at 46. His untimely death came because of years of mistreatment in Mussolini’s prisons. He had been a prisoner since 1926. In 1921 he was part of the foundation of the Italian Communist Party (PCI), after its separation from the old socialist trunk. His Prison Notebooks are the substantial part of Gramscian work. His contributions to Marxism are the subject of debate on the world’s left because of their diverse interpretations.

The Italian revolutionary died on 27 April 1937, at 46. His untimely death came because of years of mistreatment in Mussolini’s prisons. He had been a prisoner since 1926. In 1921 he was part of the foundation of the Italian Communist Party (PCI), after its separation from the old socialist trunk. His Prison Notebooks are the substantial part of Gramscian work. His contributions to Marxism are the subject of debate on the world’s left because of their diverse interpretations.

By Miguel Sorans, in El Socialista 347, April 2017. A leader of Izquierda Socialista (Argentina) and of the International Workers’ Unity-Fourth International (IWU-FI)

The Prison Notebooks are written full of ambiguities and contradictions, even in their original language, which has always given rise to various interpretations. During the post-war years, these texts were the ideological basis of the powerful Italian Communist Party and most of the other European Communists, all of them deeply reformist and Stalin’s satellites and of the bureaucracy that ruled the Soviet Union. In Argentina, they were published in Spanish in the 1950s by a group of intellectuals linked to the Communist Party, led by Hector Agosti.

After the Berlin Wall fell in 1989 and the dissolution of the USSR and the Stalinist apparatus, many of Gramsci’s texts were rescued by various sectors of the left as a quest to ‘reinterpret Marxism’. Thus, this author was vindicated by all the variants of neo-Reformism, Chavismo, Castroism, the autonomists and even by sectors of Trotskyism (especially Ernest Mandel). Gramsci thus became an additional source of reference and debate in the universities and beyond, as a ‘different’ and ‘open’ Marxism.

Who was Gramsci really and how to interpret his work?

First, we say he was an honest revolutionary, an anti-fascist, communist, and that he endured the worst conditions in prison without losing the aim to fight for socialism. But this does not conceal his political and theoretical confusions and errors.

We cannot ignore that Gramsci adhered, after Lenin’s death, to the anti-Marxist conception of ‘socialism in one country’ Stalin and the majority of the Third International launched in 1924 against the positions of the opposition led by Trotsky. This was a politically and theoretically wrong alignment. But Gramsci was never a Stalinist in the sense of supporting the bureaucratism and criminal methods of Stalin and his clique. It is even known that he sent a letter to Moscow warning of the dangers of ill-treatment of the opposition leaders. He also opposed the sectarianism of the so-called «third period» dictated by Stalin between 1928 and 1933, which was opposed to the defensive united front against fascism that Gramsci proclaimed. In 1935, he mistakenly adhered to the position of the ‘popular fronts’, Stalinism’s shift towards political unity with the socialist reformists and the ‘democratic’ bourgeoisie to govern. Gramsci spent eight years in prison, was released from house arrest already very ill in 1934, and could not learn about the process of bureaucratisation of the Soviet apparatus and its counter-revolutionary turn.

But all this does not mean we should not point out what we consider being the misconception of his thinking. To be rigorous in the analysis of Gramsci’s work, we must answer the following question: was his work right or wrong? For us it was wrong and tended towards reformist positions. That is why its ambiguities served post-war Stalinism and post-Wall neo-reformists. Those positions already existed in his texts before he was imprisoned.

One of his crucial errors was to interpret, perhaps under pressure from the triumph of fascism, that the example of the Russian (eastern) revolution could not apply to the countries of Central and Western Europe. «The determination that in Russia was direct and threw the masses onto the streets, to the revolutionary assault, in Central and Western Europe is complicated by all the political superstructures created by the superior development of capitalism, makes the action of the masses slower and more prudent, and thus demands from the revolutionary party a whole strategy and tactics much more complicated and more encouraging than those needed by the Bolsheviks”. This definition would be crucial for Gramsci. Here he already speaks of a different «strategy» than that of the Bolsheviks. That is why he would strongly argue against Trotsky and the theory of ‘permanent revolution’. From there he would develop his famous military comparison between «war of movement» (1917 Russian revolution) and «war of positions» (in Italy and the West). And he would slide more and more towards intellectual and less class-based positions and visions.

Two balances against the triumph of fascism

Gramsci took a different view of the triumph of fascism in Italy than the Third International did under Lenin and Trotsky. This is little taken into account by the followers of his work.

The Fourth Congress, in 1922, pointed out that «the objective conditions for a victorious revolution were given. Only the subjective factor was missing, a revolutionary party was missing […]. The old Socialist Party … had reformist elements in its midst that paralyzed it at every turn. …] It made no effort to betray the working class» (Resolution on the Italian Question, 1922).

Gramsci had an opposite definition. Academic and not political, since for him the defeat was because the PSI (Italian Socialist Party) «did not produce a single book»: «They did not know the ground on which they should have fought […] in over thirty years of life the Socialist Party did not produce a single book studying the Italian economic-social structure»

Differences with Trotsky

Gramsci, in his contrast between the Russian revolution and the revolutions in Europe, questioned Trotsky and his theory of permanent revolution. Theory that rejected revolution by «stages» and the government with a bourgeois sector.

«It remains to be seen whether Trotsky’s famous theory of the permanent character of the movement is not a political reflection of the general […] economic-cultural-social conditions in a country where the structures of national life are embryonic and lax, and incapable of becoming ‘trenches’ or ‘fortresses’.

In another place he said: «The theoretical weaknesses of this modern form of old mechanicism are disguised by the general theory of permanent revolution, which is nothing more than a generic foresight presented as dogma, and which is destroyed by itself, because it does not effectively manifest itself»

Wrong categories

From then on, in his Notebooks…, he developed wrong categories from the point of view of Marxism and its clear definitions in relation to social classes. For example, the weight of the «state-civil society» relationship; the need for a «historical bloc» and «building hegemony», without specifying the role of the different classes. From his scheme about the «war of positions» and a «long-term cultural change» he derived the wrong concept of «passive revolution». Gramsci said: ‘The concept of passive revolution seems to me to be accurate not only for Italy but also for the other countries that modernized the state through a series of reforms or national wars, without going through the political revolution of a radical Jacobin type.

A reformist vision is clear in Gramsci’s consideration of the possibility of a revolution without radical change, without the experiences of the Russian October and without a class-based approach. Neo-reformism is taken from all this to deny the struggle for workers’ and people’s power, replacing it with ‘building power from below’; replacing the working class with ‘civil society’ and identifying ‘historical bloc’ with poly classicist political units, popular fronts and ‘left’ governments shared with the bourgeoisie to dispute ‘hegemony’. All those ambiguities in Gramsci’s writings are those that the old Communist parties took advantage of in the 20th century and are now used by the neo-reformists in the 21st century.

1. Letter to Togliatti, Tasca, Terracini and others (Vienna, 9 February 1924), in Gramsci, Writings page 201) 2.

2. In Gramsci’s Writings, 1923, pages 168-169.

3. Notebooks… 2, pages 865-6, quoted in The Antinomies of Antonio Gramsci, by Perry Anderson, pages 22-23

4. Cahiers… 5, page 157, quoted in Leer Gramsci, by Daniel Campione, page 103

5. Notebooks…2.page 216

Annex

Gramsci’s life

Gramsci was born on the island of Sardinia in 1891. In 1911, he joined the Italian Socialist Party (PSI). After the triumph of the Russian Revolution, the PSI asked to join the Third International in 1919. In that year, the Fascist movement was also founded. The echoes of the Russian Revolution will be reflected in Italy with the revolutionary rise of the workers’ movement. In 1919-1920 there would be the widespread movement of factory takeovers and the emergence of «workers’ councils», especially in the automobile industry in Turin and Milan. Gramsci was deeply involved in this process. In 1921, differences between the PSI and the Third International arose and the reformist majority broke up. The revolutionary minority, led by Bordiga and Gramsci, founds the PKI in January 1921. In April 1922, the PSI signed a «peace pact» with the fascist movement. It would continue to strike at the workers’ movement and in October 1922, after the «March on Rome», Benito Mussolini was appointed Prime Minister. In 1924, Gramsci is elected national deputy and secretary general of the PCI. In January 1926 he drafted the fundamental documents of the ICP congress, which was held in Lyon, France. In November he is arrested by Mussolini’s government, after his parliamentary immunity is revoked. Fascism was consolidated. In prison Gramsci would write the Prison Notebooks, in over five hundred handwritten letters. In 1933 his health worsened. In 1934, he was granted parole and sent to a clinic. In 1937 he was given full freedom, but already when he was dying. His letters were compiled and edited, in 1947, after the second war, by Palmiro Togliatti, who was and was Secretary General of the PCI until his death in 1964.