19 July 2021

We reproduce the interview with Miguel Sorans, a leader of Socialist Left and the IWU-FI, by Juan Luis González, a journalist for NOTICIAS magazine.

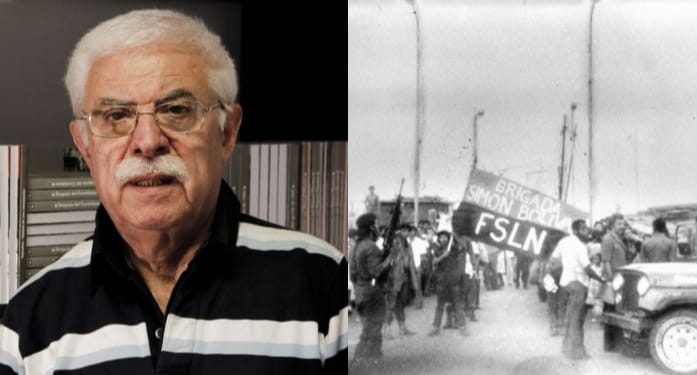

Miguel Sorans led the Simón Bolívar International Brigade. His meetings with Ortega and the details of the civil war that is now 42 years old.

Miguel Sorans fumbles with a piece of paper from his pocket and hurriedly writes: “Support from the Simón Bolívar Brigade”. The following day of the triumph of the Sandinista, an agitated crowd in the eastern part of Managua faced the Argentinian. He is wearing olive green from head to toe and carries a 32-calibre revolver in his waist. The young Trotskyist’s plan is for the international militia he commanded during the war to get public recognition from the man standing metres away. He taps the shoulder of the man immediately to his right on the stage. The notation spins until it reaches the hands of Daniel Ortega, the hero of that July 1979 for much of the world’s left. But something unexpected happens: the Nicaraguan raises his head, looks at Sorans – surprised? contemptuous? And then rolls up the sheet and throws it away. Days later, Sorans and the 200 soldiers from all over the world to fight against the dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza are expelled at gunpoint.

“That was the first repression by Ortega, who today is a dictator”, Sorans recalls to NOTICIAS, on the day that marks 42 years since the triumph of the revolution in which he took part. The militant of the Socialist Workers Party, led by Nahuel Moreno, was 32, and a prominent trade union delegate. You understand that four decades ago, the world was very different: it had just been twenty years since the Cuban triumph, and the feeling that revolution was just around the corner had not dissipated, not even with Videla’s coup. For all the world dreamers, the flag to raise was the Sandinista, which was in an open struggle against a repressive and colonial dictatorship. “The idea was to repeat the experience of the international brigades during the Spanish Civil War,” says Sorans.

Moreno, exiled in Colombia, was the one who designed a plan to support Sandinismo. Sorans was a key player in that arming: he was one of the few members of the PST – the party of choice as a target for both the Triple-A and the dictatorship – who had military and political training, and his skin was tanned after three years of living in hiding. That is why the Trotskyist left the country in hiding, via Brazil, and was reunited with his leader. After a week in Colombia, where they took part in a big fund-raising drive (Sorans says that an M16 machine gun or a Garland rifle fetched 250 dollars on the black market) and gathered public support, they travelled to Costa Rica. There Sorans became one of three leaders of a group of 80 people – there were Nicaraguans, Costa Ricans, a German and another Argentinian, Nora Ciapponi, famous for being the first woman to bring the fight for legal abortion into a political campaign – who then joined the struggle, under the banner of Simón Bolívar. By the end of the war, the international brigade would have over 200 soldiers in its ranks and three killed in action.

Interviewer: You risked your life by leaving the country and going to war. What moved you to fight in a country that was not your own?

Miguel Sorans: We were motivated by international solidarity. Dictatorships predominated, and the fall of Somoza was what it was, a fall that would weaken all the other dictatorships on the continent. And it wasn’t just a personal decision. I went as part of an international movement to play a role as organiser of the Brigade. It was a global decision of the current. Of course, one has doubts or fears, but just because you are a revolutionary, you don’t stop having fears or ignore what is at stake. Like any struggle, it is a risk, but it is a risk taken to make a change. Here we achieved that change, but unfortunately, it was not as positive as we would have liked and unfortunately, Ortega left aside those social and political demands for which the revolution was made.

I: You had the political experience but taking charge of a militia in war must have had its challenges. What was the most difficult thing?

Sorans: We knew we had something in common, an idea. Not everything is rosy, we were all of the different nationalities and some with little experience. There were details, but we tried to have a discipline for combat and acting. Sometimes we had to sleep in terrible conditions, the food was always rice; the mosquitoes were so big that they were heavy and at night the temperature reached forty degrees. The area where we were stationed in Bluefields, in the south of Nicaragua, was only accessible by boat. There was also a lot of poverty in the country. To give you an idea of the material difficulties, we couldn’t take many photos because we ran out of the film and couldn’t get any in the whole of Nicaragua.

I: How were you received by the Nicaraguan people, and by the Sandinista Front?

Sorans: That was the contrast. By the people, the reception was excellent. As Sandinismo became more and more established, our presence and our ideas were received badly. After the triumph of the revolution, many people wanted to keep their weapons, and we joined them in this demand.

Et Tu. On 19 July 1979, the last of Ortega’s Civil Guard forces surrendered. A few days earlier, the Simon Bolivar Brigade led by Sorans – another on the southern front was present, where the bloodiest fighting took place – had accomplished its aim and taken Bluefields. “The enemy’s morale was very low, and we quickly took control of the town and set up an assembly government,” says Sorans.

The Brigade’s popularity was immense. Before the end of July, in a plenary session, a dozen trade unions – which the international militia had helped to build – proposed to give Nicaraguan nationality to the Latin American soldiers. But when Sorans heard a request repeated on official Sandinista radio, he sensed something was wrong. “Simón Bolívar Brigade, Simón Bolívar Brigade, report tomorrow at 17:00 at the General Command in Managua,” was the request broadcasted repeatedly.

Until then, Sorans had only seen Ortega at the event when he tore up the paper. That call, after that incident, promised nothing good. And he was not wrong: although the SB Brigade arrived at the meeting with six of the nine top Sandinista commanders – among them the two Ortega brothers – accompanied by a demonstration of popular support of five thousand people (in a city that then had 500,000 inhabitants), the situation deteriorated. The meeting, which had begun with some tension, broke up when Sorans asked for the floor to comment that it was the opinion of the Brigade that Nicaragua should disregard the foreign debt. Bayardo Arce, the only commander from 1979 who is still at Ortega’s side today, took the microphone away from him, cut him off and called him deluded. They promised us we would meet again two days later to resolve the Brigade’s situation, but it was a trap: when Sorans and his men returned, they detained them with excuses and finally took them to the airport and deported them at gunpoint. “I was more afraid there than in the entire war”, says the man, who is now a member of Izquierda Socialista.

Sorans: I didn’t even have time to get my passport. They picked us up at two o’clock in the morning, by surprise, and loaded us onto buses without telling us where we were going. I thought they were going to liquidate us and then say it was a skirmish.

I: Until then, how did you view Ortega as a revolutionary leader?

Sorans: We respected him for having led the revolutionary process, but we had a different political conception of where the revolution had to go. Castroism formed him, and with the USSR still alive, there was a hatred of Trotskyism, although we didn’t hate them. We hoped the process would move forward we could overcome these differences; they didn’t believe in deepening the revolution, and we did.

I: Today, Nicaragua is mired in a dictatorial crisis with Ortega, in another revolutionary moment, at the helm. You looked him in the eye: are you surprised by the turnaround?

Sorans: No, Ortega’s current turn started with his treatment of the SB Brigade. We can say that this was the first repression. As soon as they came to power, Ortega governed with Violeta Chamorro, who we said had to be removed from the government because she was pro-American. Today Ortega is putting Chamorro’s daughter in prison, accusing her of being pro-American, a paradox. Though the revolution had triumphed, Ortega did not break with the bourgeoisie; He also agreed with the Church, the conservatives and the big sugar producers. What happened then announced today’s turnaround.

I: What outcome do you predict?

Sorans: I hope the Nicaraguan people will quickly kick him out, he may last a little longer, but he will eventually fall. I want to clarify that it is a dictatorship, there are sectors of the left that still defend it, but no, there is no socialism or left-wing government there. It uses the old banners of Sandinism and anti-imperialism to govern by stealing and making pacts with the big business mafias. He is going to fall; the people are going to rebel at some point. Ortega will take the place of the traitor in history. The lies he told us he then passed on to the Nicaraguan people.

I: How does it feel to have taken part in a revolution that ends in this way? Is it frustrating?

Sorans: Frustrating because it was impossible to make progress when there were extraordinary conditions to get out of misery and move towards socialism. That is frustrating, but no, I don’t think our work was in vain; it contributed in a small way to bring down the dictatorships. It was a stimulus and a joy for all the people of the continent.

I: 42 years have passed since the struggle, and, considering that Nicaragua is as it is, is your revolutionary faith still intact?

Sorans: Yes, it is still the same. This process has become bureaucratised, as happened in the USSR; that is why we follow Trotsky, who Stalin threw out for fighting for socialism with democracy. We still believe in socialism; we know it is difficult, but it is not a utopia. And we continue to FIGHT for it.