It was half past six in the morning, on the 27th of April, when the partisan group of the Garibaldi Brigade of the anti-fascist resistance detected a German convoy near the village of Dongo, a municipality in the province of Como (Italy). After an exchange of fire, the Germans agreed to negotiate. The brigade members allowed the Germans to withdraw in exchange for the surrender of all the Italians with them. At around 7p.m., as they were checking the Italians’ papers, they recognised Benito Mussolini, disguised in German clothes.

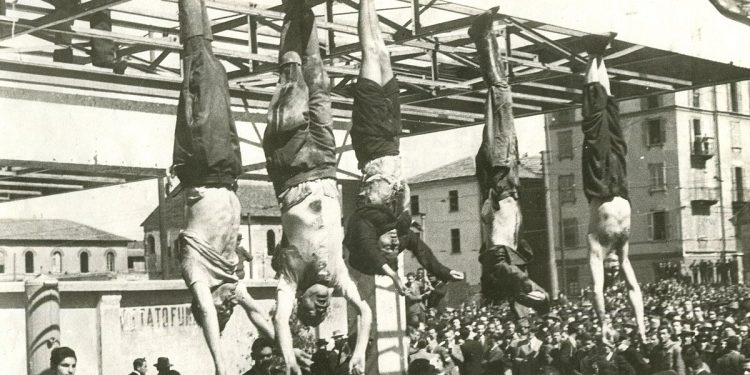

The news of the arrest of il Duce (‘the Duke‘ – the warlord), the fascist dictator who had ruled Italy with an iron fist between 1922 and 1943, was announced on the radio, along with the decision of the National Liberation Committee to execute him “like a rabid dog“. On April 28th, he was shot, along with his mistress Clara Petacci. Their bodies, and those of other fascist hierarchs, were taken to Milan and displayed in Piazza Loreto, being then hung upside down. The image travelled the world and marked the coup de grâce against fascism in World War II.

After the signing of the armistice, between 1919 and 1920, the Italian proletariat staged a revolution that shook the country. It was part of the upswing provoked by the war, which had succeeded the triumph of the Russian Revolution in 1917. In Italy, factories were taken over and workers’ councils (soviets) were formed, mainly in the industrial north, in Milan and Turin. But the treachery of the reformists in the Socialist Party, and the youth and inexperience of the new Communist Party brought the revolution to a defeat.

On March 23rd, 1919, Mussolini founded the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (‘Italian Fighting Leagues‘). The Fascist movement grew until, in November 1921, it became the National Fascist Party (Partito Nazionale Fascista) and Mussolini was elected deputy in Milan. While social democracy was lulling the workers to sleep, among the bourgeoisie, the rural and urban petty bourgeoisie, adherence to fascism was growing.

In 1931 Leon Trotsky wrote: “Fascism in Italy is the direct product of the betrayal by the reformists of the insurrection of the proletariat. Since the end of the war, the Italian revolutionary movement had been on the rise and by September 1920 the workers had reached the point of occupying enterprises and factories. […] Social Democracy was afraid and retreated. […] The crushing of the revolutionary movement was the most important premise for the development of Fascism“. (1)

In 1942, the imminence of an Allied invasion of Sicily, the hardships of the troops, and the poor living conditions at home, fuelled growing popular unrest. The year culminated in the beginning of the activities of left-wing organisations, underground workers’ parties and trade unions. The big strikes in the Fiat factories, in Turin, began to spread to other cities. By the first months of 1943, the strike movement against the war and material hardship dominated the industrial north, clamouring with economic and pacifist demands in defiance of the fascist regime. The Soviet victory over the Nazi armies at Stalingrad in February strengthened the anti-fascist resistance.

In 1945, amid the collapse of the Nazi armies, Mussolini travelled to Milan in an attempt to negotiate his surrender to the Allies. An immediate and unconditional surrender was demanded. He rejected it, and when he attempted to retreat northwards he was stopped by the partisans who controlled the area. His assassination and Hitler’s suicide two days later on April 30th marked the end of Nazi-fascism in World War II.