By Nicolas Nunez, a leader of Socialist Left (IS) and the IWU-FI

15 August 2023

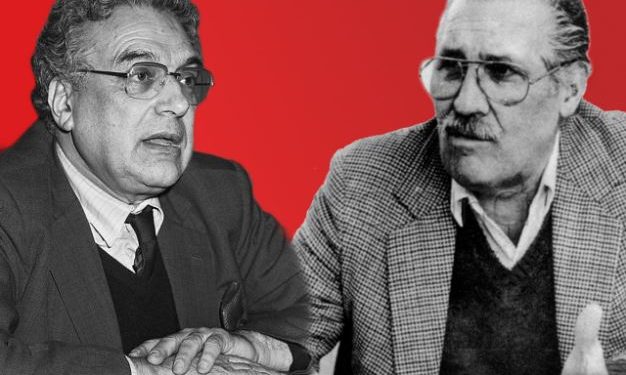

Through “Ideas of the Left”, the leader of the PTS (Socialist Workers Party) and the Trotskyist Faction – FI, Christian Castillo, published “On the 100th anniversary of Ernest Mandel’s birth”, where he develops a vindication of contributions and an enumeration of criticisms before the trajectory of the historic European leader of world Trotskyism. The text is presented as an extension of the intervention that Castillo developed on 30th March at an event in homage to Mandel organised by Poder Popular (Popular Power), Marabunta and Economists of the Left, with referents that vindicate the trajectory of the Belgian Trotskyist leader.

The document fails to take a position on the essential question: are his militant trajectory of more than half a century in Trotskyism and his legacy essentially correct and progressive to continue building revolutionary Trotskyist parties, or, on the contrary, does it represent an accumulation of errors, capitulations and revisionism from which it is necessary to delimit oneself to promote the reconstruction of the Fourth International? Is it that during a period of his trajectory Mandel’s political answers “were not up to the circumstances” as Castillo points out, or that on the whole it is a trajectory in which the rupture with the pillars of revolutionary Marxism and Trotskyism and capitulations prevailed? In his text, the leader of the PTS not only omits to take a position on these questions but as of high praise (“he developed the most prolific theoretical work” among the leaders of post-war Trotskyism), he points out that he feels closer to Mandel’s writings than those who are militants in what would represent official Mandelism. Simultaneously, key elements of the Mandelist current’s bearings are systematically swept under the carpet.

Without delaying in giving our answer to these questions, we will point out the systematic capitulation to the reformist and traitorous leaderships; the abdication of building militant political organisations based on democratic centralism -at the national and world level-; the renunciation of the fight for the workers’ government, and methodological impressionism that also led it to embellish the capitalist system in its epoch of decadence; our Morenist current, expressed in Socialist Left and the International Workers’ Unity – Fourth International (IWU-FI), understands that the reconstruction of the Trotskyist movement at world level requires a clear delimitation of the work of the man who, for decades, was the main leader of the Unified Secretariat since it considers that taken globally his legacy provides wrong coordinates for the construction of revolutionary organisations in the present.

Before we enter into the polemic with Castillo’s text, let us point out that historically our current has recognised the intellectual weight and militant commitment of a personality of Mandel’s stature, a leader who suffered Nazi persecution, who on different occasions was forbidden to enter different countries, who was personally involved in various revolutionary processes and who effectively made theoretical contributions from Marxism which gained wide circulation even outside the Trotskyist movement. Nahuel Moreno and Mandel’s systematic polemics always took place from a place of respect. And we can even say that between Morenoism and Mandelism there were (as we will see below) very firm and deep debates, but clear and fraternal. Something that does not happen –unfortunately- with the comrades of the PTS leadership who have been for thirty years building a school of falsifying Moreno’s positions and avoiding answering the debates raised. Even more, they did not miss the opportunity to do it in this review of Mandel’s work.

In “A scandalous document”, the 1973 document of polemic with Mandel renamed as “the Morenazo” by the PST militants of the time[1], the Argentinian leader began by recovering Trotsky’s teachings on how to lead a political discussion, and in particular, his invocation not to lose sight of the reality that the working class has a limited number of hours for reading and engage in political debate, and therefore urges not to go off into the human and the divine, but to focus on “the concrete evaluation of the facts and the political conclusions”[2]. Taking this methodological criterion, we interpret that for the PTS, what is central and decisive to be criticised concerning the Mandelist positions are the aspects summed up by Christian Castillo. Namely: the class definition of the States in which the bourgeoisie was expropriated in the post-war period; the characterisation at the beginning of the 1950s of a period of “war-revolution” which made a world conflagration between the United States and the Soviet Union imminent, and the political-organisational definition linked to making “entryism sui generis” -dissolving itself- in the Communist and social-democratic Parties; the definition of a new stage of the capitalist system in which a new growth of productive forces would have unfolded; and to a lesser extent Castillo develops Mandel’s support and impulse in the second half of the sixties to the guerrilla drifts in Latin America; a late position of embellishment to the reform process promoted by Mikhail Gorbachev in the last days of the USSR; and finally a vindication of universal suffrage and parliamentarism as necessary instruments of a “post-revolutionary State”. On this last point and that of entryism, Castillo will take the opportunity to amalgamate positions with Nahuel Moreno’s remarks to disfigure the latter’s legacy, something we will return to at the end of this text.

A trail of “scandalous” omissions

Let us begin by saying that the selection made by the PTS of its differences with the Mandelist legacy is striking in its omissions.

Let us start from the central point: Castillo does not understand it necessary to delimit himself for the fact that Mandel, in his role as the key leader of the Fourth International, together with Pablo, since the post-war period, and then since 1963 of the Unified Secretariat of the Fourth International (FI), again with Pablo, Mandel headed the sector of Trotskyism that was falling into increasingly revisionist and opportunist positions, betraying the workers’ revolution in Bolivia in 1952 by supporting the bourgeois government of the MNR nationalist movement[3], renouncing the construction of revolutionary parties, supporting bureaucratic leaderships like Mao and Castro, leading the Fourth to crisis and division since the fifties, to the dispersion of the Trotskyist movement that still has not been overcome. The article also fails to point out that Mandel played a central role in transforming the Fourth International into a mere regrouping of tendencies, without debate or programmatic cohesion, coherent with his definition of ceasing to promote the building of Leninist parties and going on to broad “anti-capitalist” parties-movements.

It is worth remembering that it was this theoretician of the US who began to suggest that Lenin and Trotsky would have fallen into the “substitution” of the working class, defining that both would have gone through some “dark years” of their intervention in 1920-21 regarding the central role played by the Bolshevik Party in leading the defence of the revolutionary process. Thus echoing, or allowing to run, the recurrent revisionisms that hold the author of “The State and the Revolution” and the leader of the Red Army responsible for the subsequent rise of Stalin. It is striking here that, for a current that usually presents itself as deeply concerned about the link between the political and the military, it is not worth pointing out that Mandel has repudiated the political-military measures for the preservation of the Soviet State defended by Lenin and Trotsky[4].

Well then, let us point out that in the antipodes of Mandelist revisionism, Trotsky bequeathed us key points, such as those in “Dictatorship and Revolution” (1937):

“The revolutionary dictatorship of a proletarian party is not for me a thing that one can freely accept or reject: it is an objective necessity imposed on us by the social realities of the class struggle, the heterogeneity of the revolutionary class, the necessity of a revolutionary vanguard selected to ensure victory.”

Mandel’s theoretical construction, from his work “Socialist Democracy and Dictatorship of the Proletariat” (1977) is built to a large extent on burying these clear Trotskyist definitions, and counterposing them with a dismissal of the role of the party, and a glorification of bourgeois liberties, in the framework of a general capitulation to “Eurocommunism”[5] which was a tendency in the Communist Parties that not only repudiated the Stalinist bureaucracy, but the revolutionary perspective in its entirety. Another situation Castillo fails to mention.

Nahuel Moreno’s work “The revolutionary dictatorship of the Proletariat” [6] represented the principled answer of our current to that turn of the US headed by Mandel and the document with which it proposed to give battle in the XI Congress of the Fourth International in 1979. But here, another of the facts omitted by the PTS in its homage crossed the path.

Indeed, in his text, Castillo circumscribes the relationship of Mandelism with the reformist, Stalinist, petty-bourgeois and traitorous currents as mere “generation of expectations or embellishment”. But the reality is that it went much deeper than that. In the example to which we will refer specifically, in Nicaragua, Mandel supported the bourgeois government of Sandinismo with the anti-Somocista opposition of Violeta Chamorro and Alfonso Robelo of July 1979. As the PTS leader points out in a footnote to his text, he defined it as a “workers’ government” but did not limit himself to that alone: he also supported Daniel Ortega’s imprisonment and then expulsion from the country of the militants – many of them Trotskyists and others not – of the Simon Bolivar Brigade promoted by Morenoism, which had fought against the Somocista army and had initiated a process of exemplary workers’ organisation independent of the co-government with the bourgeoisie of the Sandinista leadership. Faced with this flagrant violation of basic revolutionary principles, the Morenist current withdrew from the Fourth International, while the XI Congress ratified support for the bourgeois government of Ortega and the business people and the expulsion of the Brigade[7]. Nor does Mandel, the leader who criticized Trotsky to defend programmatically that in a revolutionary process full political freedom should be guaranteed even to the bourgeoisie, deserve a mention for the PTS, since he has found no contradiction between that position and defending the repression and expulsion of Trotskyist militants in Nicaragua. Is it not necessary to educate the new generations joining the Trotskyist movement that perhaps its most visible leader after Trotsky’s death considered it correct for a bourgeois government to detain, beat and expel revolutionary militants who promoted a policy of building the party for the working class within the framework of a revolutionary process?

We must add to the scandalous omissions of the homage to Mandel by the PTS that they do not mention the betrayal of the Bolivian Revolution of 1952, where Mandel and Michel Pablo promoted the policy of supporting the bourgeois government of Paz Estenssoro, while Trotskyism had mass influence, co-led the COB, and could influence the outcome of events in which the workers had -as they were armed- destroyed the bourgeois army and after that still had the weapons. The right call was to fight for “All power to the Bolivian Central Union (COB)! Should we not teach those who join Trotskyism -still a minority in these latitudes- that one of the most powerful workers’ revolutions of the continent, with a strong presence of Trotskyists, played a lamentable role under the responsibility of leaders like Mandel and Pablo?

In sum, Castillo correctly points out that in the 1960s/1970s, Mandel supported the thesis of universalisation of the tactic of guerrilla warfare for all of Latin America. But he does not link this deviation to the previous and subsequent ones, of Mandel and the Mandelists, who have built a saga -continued to this day- of following the concerns of vanguard sectors and capitulation to the reformist or counterrevolutionary leaderships of the moment. Be it Tito, Mao or Fidel Castro, be it pro-guerrilla leaderships (1960/70), Eurocommunist (1970/80), Zapatista (1995), pro-Lula and pro-Chavist (2000′ onwards), there was always at all times and places some Mandelist organisation that supported them. The very anti-Leninist party movement turn of the broad parties that directly inspired Mandel before his death is also inscribed in this impressionism and search for permanent shortcuts in the construction of a revolutionary organisation that has been part of the DNA of Mandelism against the teachings of Lenin and Trotsky. And with this, we do not deny the need to develop specific tactics of unity and confrontation with those currents, as Morenism has done throughout its history, but as a rule, at the service of unmasking them and not giving them political support. That is why we highlight the omission of the PTS from capitulations of all kinds and colours, such as those mentioned above, or others that could be enumerated, such as the incorporation of one of the sections of the Mandelist IC into the executive of the Lula government with a minister (of “Agrarian Development” in 2002).

The importance of the debate on Productive Forces

In his article, Castillo summarises that Mandel advanced towards a definition of a new stage of development of capitalism, “neo-capitalism” or “late capitalism”. This categorisation crossed the borders of the Trotskyist movement, and was adopted by influential theoreticians of academic Marxism such as Fredric Jameson, who -synthetically- defined “postmodernism” as “the cultural logic of late capitalism”. In order not to overextend this polemic, we will not enter into a debate with this theoretical construction around a new stage of capitalism beyond what we consider its central aspect: an economic and technicist revisionist conception of the productive forces. Mandel declared “mistaken” the definition of the Transitional Program that “the productive forces of humanity have ceased to develop”. We mentioned this in the “Morenazo” as the material basis of the colossal differences in the political definitions and the construction of revolutionary organisations. Although Castillo reaffirms that for his current the growth of the productive forces identified by Mandel should be proposed as “partial development of the productive forces” (the PTS launched this definition long ago), he reveals being closer to Mandel and farther from Trotsky and the first four congresses of the Third International, given that he essentially coincides with the economic conception of the productive forces by taking as a sole parameter economic growth, more precisely, the GDP of the imperialist powers[8]. Marx, Trotsky and Moreno start from the facts of reality regarding the concrete conditions of people’s lives, which obviously, as Moreno documented in the sixties and seventies and we do now, are worsening day by day for the workers and people. Why is this point important? Because to our understanding, which we believe is the one that most faithfully represents the Marxist conception that understood the working class as the main productive force, the development of this variable is not just one more statistic for the UN and World Bank charts, but rather it gives an account of the strategic sign of whether or not we are in a revolutionary epoch (unstable, of the decadence of the current regime of production and impossibility of granting structural concessions to the working majorities) or a reformist one (of gradual, orderly development and cession of rights).

Therefore, the consequences of these definitions, let us say that the Mandelist conception of capitalism that developed the productive forces leaves the “Transitional Program” and the perspective of “Socialism or Barbarism” without material support, and was consistent with a strategic definition in which, since what prevails is the increase of consumption and not the high cost of living, the central issue was the ideological dispute oriented towards the vanguard. The Trotskyist and Morenist conception, on the contrary, understood and understands that capitalism only produces a growing poverty, and therefore it is of key importance the construction of Trotskyist revolutionary parties for action and the development of the mobilisation of the masses to link the struggle in defence of their living conditions with the fight for the workers’ government, and to win the vanguard to carry out that task together with the revolutionary party. Castillo also does not take a position on whether or not he also feels “closer to the writings” of Mandel in his conception of the work on the working class and the vanguard phenomena, and his strategic abandonment for more than half a century to the building of Trotskyist parties throughout the world.

But, we must add that the productive forces, apart from the human component and technique, have a third pillar: nature. Already in Marx, there is the indication of the transformation of productive forces into “destructive forces” and that capitalism destroys the two sources of its wealth: workers and nature [9]. It would be anachronistic to criticise Mandel’s definitions of post-war capitalism with the scientific evidence we have today. But the PTS writes from a present in which -outside the climate denialism of alt-right and trumpists- we have not only sufficient empirical evidence regarding the course of climatic and environmental catastrophe to which capitalism is leading us, but also more precisely from a location provided by diverse scientific fields regarding the moment in which the qualitative leap of environmental destruction [10], i.e., the destruction of productive forces. The “post-war boom” that Mandel and the PTS point out as partial development or “relative growth” is precisely that of the destruction of productive forces.

To maintain a definition of productive forces based on the increase of GDP, when imperialist capitalism with its logic of permanent accumulation can well “grow” until it pushes humanity towards the very risk of its extinction, ends up demolishing the strategic importance of this category as an index of the historical epoch in which the class struggle is developing. The almost null importance given by the PTS to the intervention in spaces of socio-environmental mobilisation such as the Coordinadora Basta de Falsas Soluciones (No to False Solutions Coordinator) in Argentina perhaps has its origin in its misunderstanding in a Marxist key of the importance of the environmental dimension for revolutionary strategic thought. But it must be said here that Mandel, despite the economism of his definition of the productive forces, did initiate a course of elaborations within the US that decanted into the foundations of the “ecosocialist” tendency, which, as could not be otherwise, was born and grew with the programmatic limitations proper to his current: separating the tasks of the struggle against environmental destruction from the fight for workers’ governments and the construction of revolutionary parties[11].

Once again on “objectivism” and the “democratic revolution”.

In his article, Castillo identifies that “objectivism” would have been one of the methodological problems present in the work not only of Mandel but also of “a large part of the leaders and currents of post-war Trotskyism”. As could not be otherwise it is also a criticism in which the PTS usually amalgamates Nahuel Moreno’s positions.

If by objectivism we understand a theoretical development which takes some element of the material-objective base (economic, technological, etc.) and gives it the scope to determine decisively and mechanically superstructural, political phenomena, or the historical development itself, then we will say that yes, indeed Ernest Mandel has gone down this road over and over again. From the frictions between American imperialism and the USSR, he inferred an imminent state of war that justified the long “sui generis entryism” in the CP and SP, with the expectation of their transformation into revolutionary leaderships. As we indicated, from the economic growth and some certain technological developments, he derived the resumption of the growth of the productive forces under imperialist capitalism. From the majority and historically progressive character of the working class and the “true” revolutionary program, he inferred that universal suffrage would be a privileged tool of the “post-revolutionary State”, raising in passing to the level of a categorical-moral imperative the defence of bourgeois liberties, beyond the concrete and real conditions of the struggle of the classes and their institutions in each situation.

From the tasks of expropriation of the bourgeoisie that were carried out in different countries, Mandelism ended up concluding the revolutionary character of their leaderships (Tito, Castro and Mao). From the social basis of the workers’ states (state ownership of the means of production), Mandel reviewed all of Trotsky’s positions in this regard to deny the restorationist character of the Soviet bureaucracy [12] (not mentioned by Castillo).

The problem with the amalgamation and falsifications of the PTS is that in each one of these historical debates, Morenoism had an opposite position -and a method-. We will enumerate two of the amalgamations that the PTS makes in its article.

First, the brief (between 2 and 3 years) Morenoist experience of entry into the Peronist trade union organisations, in the framework of a bourgeois political movement that was banned and had no political centralisation so that the tactic of linking up with the Peronist working class was applied without having to adopt any political definition imposed by any Peronist hierarch or by Juan Domingo Peron himself, and based on keeping its publications and independently sustaining the construction of its revolutionary party. A completely different political approach was the dissolution for eighteen years of the European Trotskyist militants in the parties of Stalinism and social democracy because they were going to become revolutionaries. The equalisation that the PTS tries to establish does not stand up to the slightest debate.

Second, amalgamating the capitulation of Mandelism to the democratism of Eurocommunism and the development of post-Marxism (Laclau, Mouffe) with Moreno’s characterisation of the process of Latin American dictatorships, does not resist any serious analysis either. As much as the PTS has been beating the patch of the “program of the democratic revolution” for 30 years as Moreno’s supposed etapism and error, such a thing does not exist, and we are still waiting for them to present a case in which our current has supported a bourgeois government as a necessary step, or “democratic stage” of the socialist revolution, somewhere in the world [13]. Without digging too deep, and even though it is not mentioned in their article, they will count on several capitulations of this type to the credit of Mandelism, as we have already mentioned.

In conclusion and summary, it gives the impression that the sectarianism, virulence and systematic falsification of Nahuel Moreno’s positions by the PTS, are the other face of the opportunism with which this organisation has approached the Mandelist legacy.